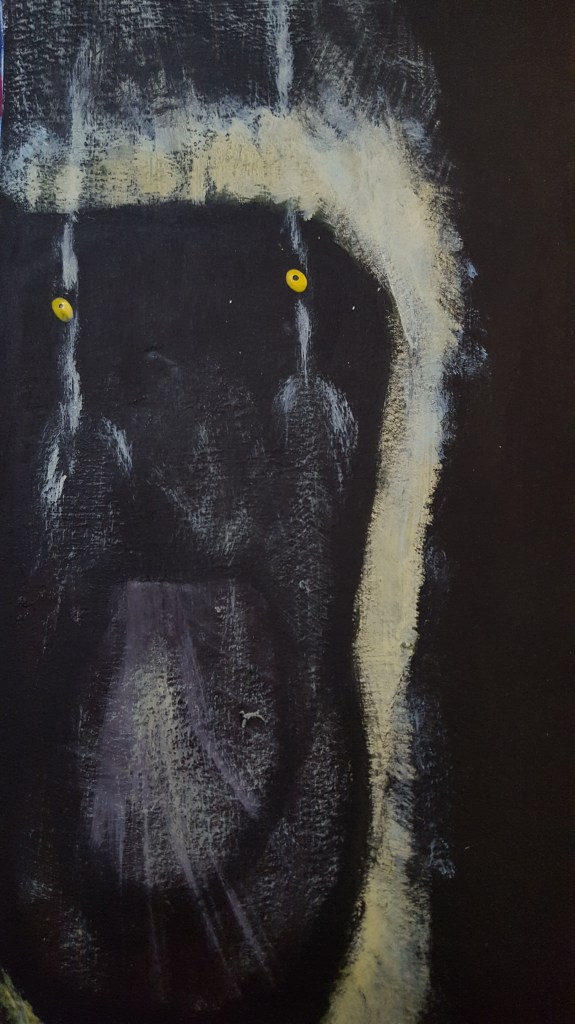

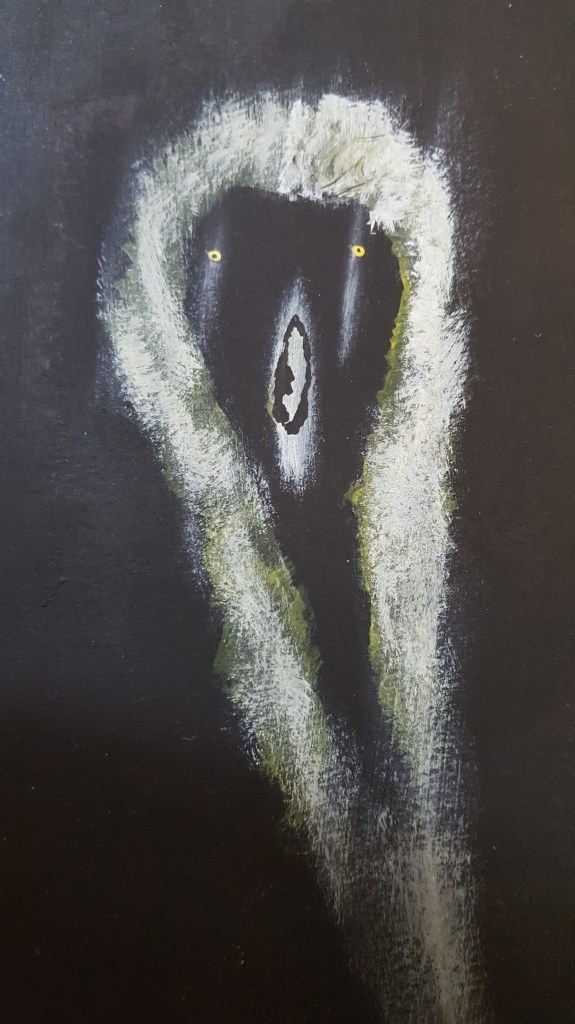

In my last year of college, I took a creative writing course called, “Writer as the Outsider.” I only remember one assignment: we had to write a short piece about our life, kind of like a micro-memoir. I wrote a story about a child whose mother shapeshifts into a distorted, grotesque version of herself every night; the house changes too, as if reflecting the mother: the floors become uneven, the walls shudder and twitch, the windows become eyes. The child’s world becomes a nightmare.

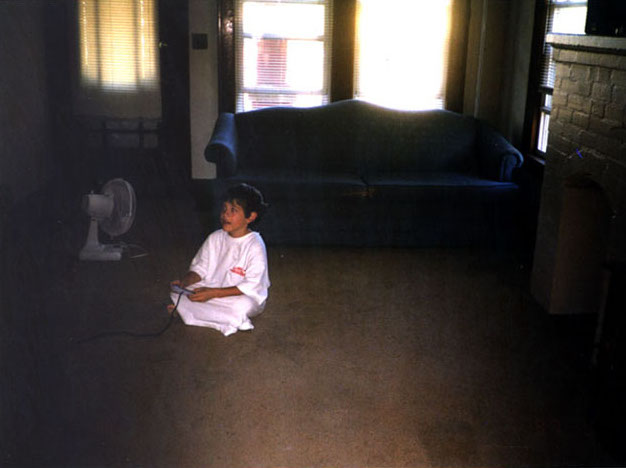

One night, the child and his brother are awoken by loud music. They know that sleep is impossible, so when the mother steps outside to smoke, they climb out of their beds and tiptoe into the living room like two little spies. The older brother carefully rotates the black stereo dial counterclockwise while the younger brother keeps watch. The balance is tricky. If they lower it too much, their mother will notice, which would lead only to disaster.

What happens next is unclear, because the child wakes up in the morning as if the night never happened. Something erases it from his memory, a protective amnesia that makes him forget all that occurred, so when it happens again the following night, it is as if it is happening for the first time.

At school, the child asks his teacher if he can go to the restroom. With her permission, he walks down the hallway and slowly enters the bathroom. He crouches down to make sure the stalls are empty, then he stands at the mirror and rubs his fists against his eyes until they turn red. (Sometimes, he rubs markers on his fingertips to ensure a reaction. He does not know why he does this.) Then, he goes to the nurse’s office. She concludes that he has pinkeye and sends him home, where he spends the rest of the day with his mother, who is still sick from the night before.

In the story, both the child and the narrator do not (or cannot) make any explicit connections between any of the events in the story. The child is too young to comprehend his situation, beyond the realization that it does not feel good. (In fact, it feels so bad that he is often sick with no discernible cause. He has stomach aches or hives, or he complains that he “just doesn’t feel good” until he is taken to the doctor, where he is perpetually prescribed liquid amoxicillin, which he learns to love the taste of, like a milky cherry strawberry dream).

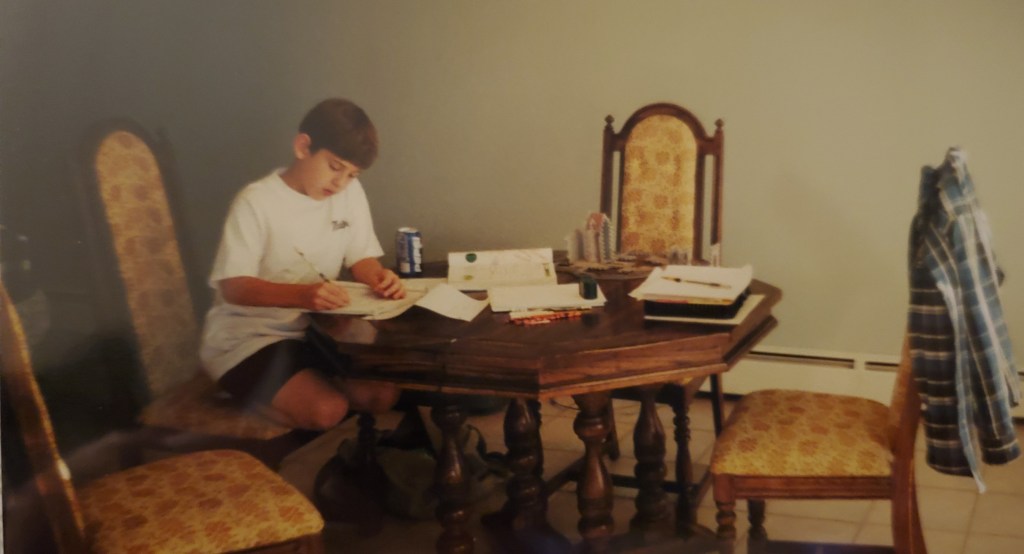

I cannot remember how I ended this story, but I remember what happened in the middle. After I wrote the childhood scenes, something in me burst open. I was entranced, writing as if speaking to myself from the outside. I no longer have the original copy of the story, but it went something like this:

You pay for people when you can’t afford it. You give people rides even when you don’t want to. You help everyone but never ask for help. You are addicted to giving. You leave yourself with nothing. You abandon yourself.

Even though it was barely a page long, I felt a strange sensation about what I’d just written: pride. What I had written had actually moved me, but the process was so mysterious. Where had it all come from? It was like the momentum had been building up for years, line by line, until the whole thing snapped like a rubber band and spewed out of me. I was accustomed to improvising with music, not with words on a page, and I was too scared to edit it, fearing I would ruin its flow. At the time, I thought the whole piece was far too fragile to revise. But the only fragile thing was me. I was too scared to read it again, awed and yet viscerally afraid of the truth.

For the second half of this assignment, each student had to meet privately with the instructor to discuss their piece. I liked my instructor, but I had no idea what to expect. What would we talk about? The story? My grade? The quality of the writing? Oddly enough, even though my piece was vulnerable and honest, I approached our meeting with only a little hesitation. I knew that once she’d read it, everything would already be out in the open; there would be nowhere, and no reason, to hide.

It was a Wednesday afternoon, and the spring sun wrapped the creative writing building in a soft pewter glow. As I walked into my teacher’s office, I hovered in the doorway. The moment she noticed me, she smiled and said, “So does your mom still drink?” I laughed, nodded, then sat down. Then, she started telling me about her mother, who had been quite the drinker herself.

We spent the entire meeting talking about being children of alcoholics, and she told me that the middle section—the “You-You-You” part—made it abundantly clear that I was a child of an alcoholic. In the other sections, I had (clumsily) attempted to be cagey by never actually mentioning alcohol or drinking, but in that middle section, she saw all the familiar signs: the self-sacrifice, the loneliness, the regret, and of course, the codependent rage. And I imagine, on some level, she also recognized herself.

During our meeting, I’d felt seen in a way that I rarely had before. I hadn’t really discussed much of my family history with my friends, and as a child, I didn’t know anyone else with alcoholic parents. It was so relieving to speak (and write) about something that had weighed on me so heavily. It was like a brick had been dislodged from my skull. My memory is fuzzy, but I am fairly certain she encouraged me to keep working on my story, or, at least, to keep writing. But I assumed she was just being nice (She probably says that to everyone). So, as always, I threw the pages away. I kept the file on my computer for a while, but eventually—perhaps in a misguided attempt to move on—I deleted that too.

After college, I attended two bouts of grad school, where I wrote countless papers, both personal and academic, but whenever my writing was praised, I devalued any and all positive feedback, and I invariably threw my papers away. I repeatedly sought confirmation that I was not just a bad writer, I was not a writer at all. Even when professors offered support and encouragement, I mentally twisted their words into criticisms. And, once I drew my conclusions, I had to throw my papers away. I never allowed myself the time or space to reconsider.

This act of compulsively and impulsively disowning my work was indeed destructive. I denied my joy and disowned my dreams. But if I had kept those papers, I would have quite a collection by now. Would they be worth sharing with anyone, or even rereading? Probably not. But their collective presence would form a written chronicle of my academic history, and, more importantly, they’d represent a physical testament to my growth, and my life, as a writer.

I can see it now: I am sitting at my computer, stuck on some piece of writing. My eyes are dried out; my head is getting heavy. I am tired. Then, I look over at a large stack of papers resting on my shelf. They are crinkled, smudged with ink, covered with red scribbles. They are not pretty, but they remind me that I have always been able to write my way through anything, be it a dissertation, a paper, a poem, a dream. I know that this feeling will pass, and that regardless of my self-doubt and confusion, I will finish whatever I am working on. I will keep writing. I will make it through.

And just like that, the stack would grow.

Although I cannot commit to printing out everything I write, I can no longer deny the fact that I thoroughly enjoy writing. And I have learned how to accept praise without needing to belittle it. I can take in good feelings; I don’t have to snuff them out anymore. It’s taken time, energy, and thought, but it has changed. I have changed. I am no longer a mysteriously sick child who rubs his eyes to stop himself from seeing the truth. And I no longer have to erase who I am, what I’ve felt, and what I’ve seen.

Writing has allowed me to reclaim myself, by which I mean writing has helped me to create myself. And it has helped me understand why I couldn’t accept praise for so long. The truth of it is, there was no me there to accept it. Who was being praised, the person who spent hours agonizing over a paper just to please a professor? Was that really an authentic piece of expression? Of course not. So, in a way, my compulsive rejection of praise makes sense to me. Back then, I was still performing, overachieving, trying to be liked. But I don’t have to please anyone anymore. I can write for myself and from myself—from the me that actually exists now.

But I have to admit, as joyful as the process of writing is, every time I get close to finishing something, a murky pool forms inside my chest. It’s like an oily rain puddle on the asphalt, it’s wet and dirty (and certainly non-potable), a mixture of sadness and loss tinged with regret. It’s too late now, it’s over, I’m defeated; I could’ve done a better job, but I didn’t.

Fortunately, this convoluted mixture of feelings never lasts for long, because when I do finally let these things go, when I finish these stories and make some sense of myself, my body begins to calm down, to get quiet. And it must be quiet for me to sleep. Quiet in my home, in my mind, and in my heart.

And it is quiet enough, now. I can finally sleep.

Note: A version of this piece was previously published on my old Substack in 2024.

Leave a comment